Alexander Graham Bell goes digital

By Sally Holland, CNN

updated 12:50 PM EST, Tue December 27, 2011

Washington (CNN) -- Voices recorded by inventor Alexander Graham Bell more than 125 years ago are being heard now, thanks to digital imaging technology.

"It's not high fidelity, but you can definitely figure out what they're saying," said Carl Haber of Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, one of the scientists working on the project in a laboratory at the Library of Congress.

The early audio recordings were made during an intensely competitive time, when scientists were racing to improve on Thomas Edison's phonograph, which was invented in 1877.

Scientists like Bell, who worked at his Volta Laboratory in the Georgetown neighborhood of Washington, were looking to improve both the quality of the phonograph and the nature of the sound to make the product commercially viable.

"I think this is a very critical episode in the history of American invention and innovation and it highlights an otherwise unknown aspect of Washington, D.C., at the end of the 19th century as the center of invention and innovation," said Carlene Stephens, curator of the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History.

Bell sent recordings to the Smithsonian in the 1880s for safekeeping, and to prove his scientific finds in case of patent questions.

But there was no playback device, so "the collection has been silent," said Stephens.

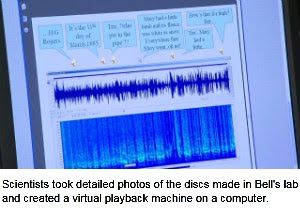

Enter modern-day scientists Haber and Earl Cornell, who took detailed photos of the discs made in Bell's laboratory and created a virtual playback machine on a computer.

"To be or not to be, that is the question," begins one of the recordings from a green wax disc that scientists believe was recorded in 1885. The male voice reading the famous quote from Shakespeare's Hamlet is muddled, but understandable.

On a glass disc recording from 1884, a voice can be heard saying the word "barometer" several times. And on another type of wax recording from 1885, a man is heard reading a description of a cotton factory in New Hampshire.

To get the audio from the discs, the Berkeley scientists put them on a turntable. As the disc slowly turned, as many as 18,000 images per rotation were recorded in the computer. The images were then stacked up to create a digital profile, which, when read by the computer, played back the sound.

"These technologies are very fast and these computers are fast," said Haber. "Ten years ago, we would be struggling with computer storage and computer speed. Today, commercial technology is up to this task."

There is no physical contact with the historically valuable discs, which helps to protect them for the long term.

The scientists in the 1880s experimented with a variety of experimental mechanisms, many of which the Smithsonian has in their collection. Each disc or cylinder plays differently.

"It turns out this record was designed to play from the inside-out, so that's backwards from how we normally play a record," said Haber, showing reporters the disc.

After the Berkeley Lab scientists had photographed that record, they reversed the information in the computer to play it.

Although the scientists at Bell's Volta Laboratory would have been working on a playback device as they were making the recordings, none of those made it into the Smithsonian's archives.

Three times during the 1880s, Bell sent sealed tin boxes to the Smithsonian Institution with objects and newspapers to prove that his laboratory had made certain discoveries by certain dates in case a patent dispute arose. None ever did. The sealed boxes were opened for the first time in 1937 in the presence of Bell's family.

Bell also donated materials to the Smithsonian during the early 1900s, when he served on the governing board of the museum.

Those items, along with materials from Emile Berliner, a competitor of Bell, are stored at the National Museum of American History. Berliner is credited with inventing the gramophone, the first commercially successful disc and playback machine.

The museum has about 400 early audio recordings made between 1878 and 1898.

This is Anderson's real Christmas!

No comments:

Post a Comment